In January 2022, a placid patch of the ocean’s surface near the islands of Tonga suddenly exploded with activity. After a month or so of activity, an underwater eruption of unprecedented scale from the Hunga volcano blasted ash up through the water column and more than 30 miles into the air, where it quickly spread out in a billowing plume spanning hundreds of miles.

The blast was so powerful that it rang Earth like a bell; it produced a shockwave that circled the globe multiple times and released a sonic boom heard as far away as Alaska. The eruption also triggered a tsunami that affected coastlines across the Pacific Ocean and made waves recorded in Japan, North and South America, and Antarctica.

Quite by surprise, scientists discovered that the eruption also had an underwater aftermath, recently described in a paper published in the journal Nature Communications Earth and Environment.

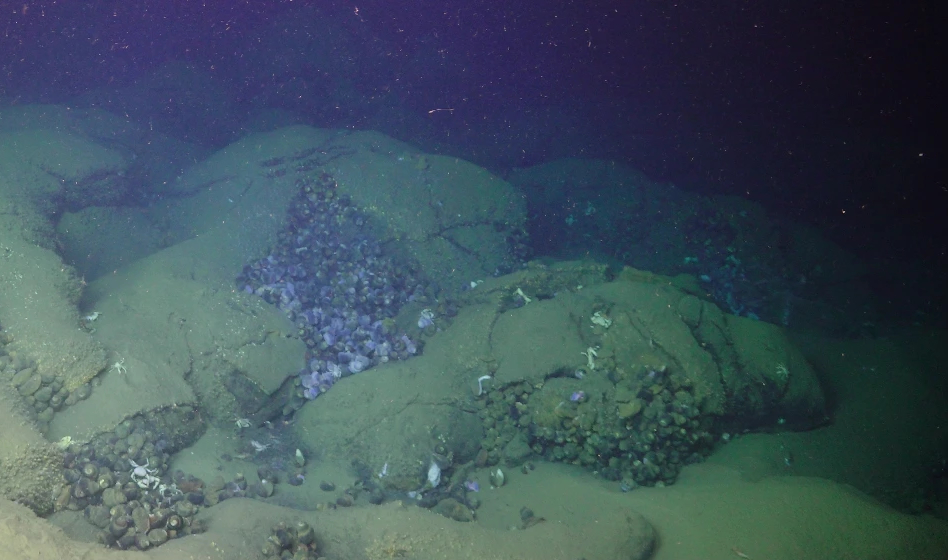

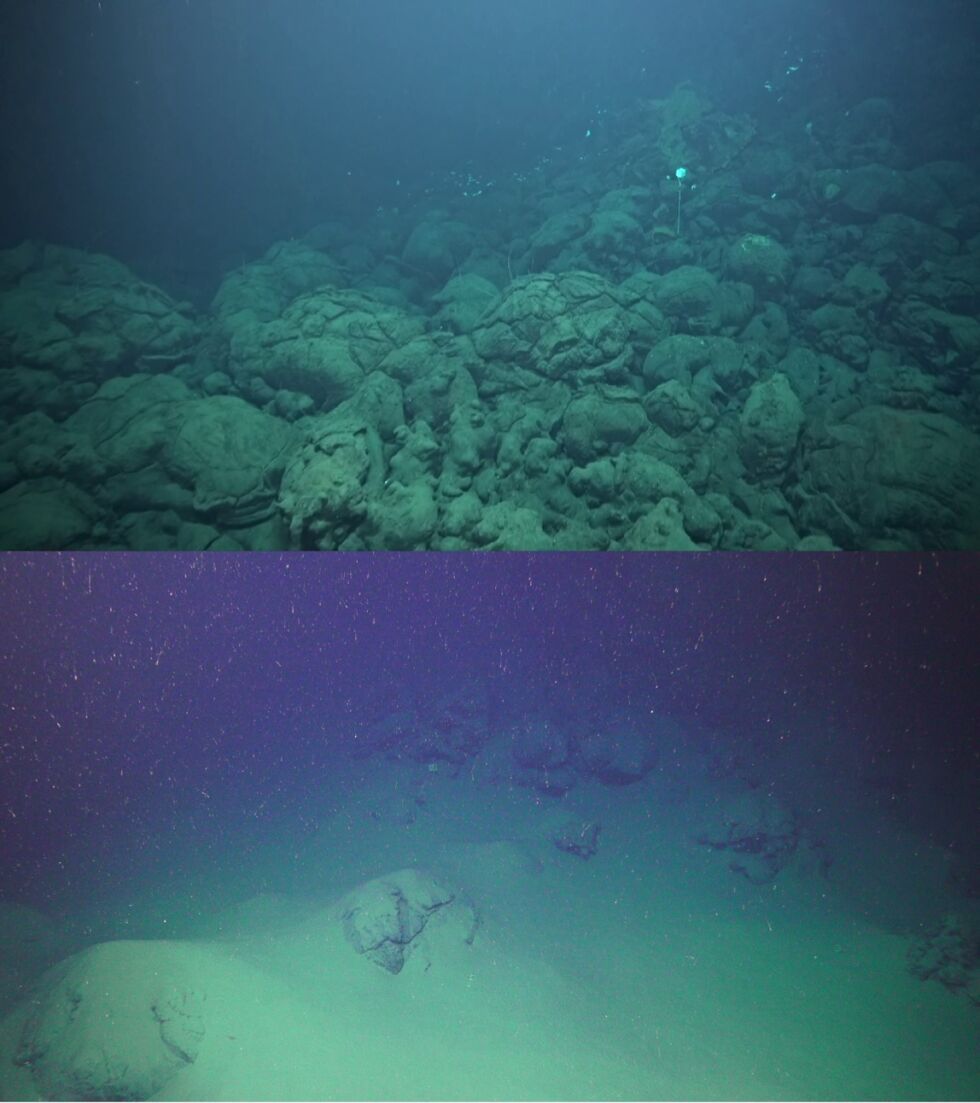

The Tahi Moana hydrothermal vent field, pictured here, was observed covered by up to six inches of ash in some places. Some snails and mussels in this region managed to survive the eruption and its aftermath.

As part of a fortuitously timed expedition, a team of researchers set sail to the Lau Basin––a large underwater area surrounding Tonga where two tectonic plates meet––in April 2022. They aimed to study creatures around deep-sea hot springs. But when they arrived, they found the region strewn with the creatures’ remains instead.

“We didn’t expect to see much, if any, fallout from the eruption because it was a few months later, around a hundred miles away, and more than a mile deep,” said Shawn Arellano, an associate professor at Western Washington University who jointly led the expedition with Roxanne Beinart, an associate professor at The University of Rhode Island. “So we were really surprised by the level of the impact we saw.”

Looking through the eyes of an underwater robot, they saw a blanket of ash up to five feet thick covering the ocean floor––a never-before-seen phenomenon. Local populations of animals, including vulnerable mussels and snails on the Red List of endangered species, were wiped out, either buried alive or unable to acclimate to their dramatically altered conditions.

Similar catastrophic events appear in the fossil record, but scientists seldom have a chance to gather real time observations.

“There are very few modern examples of observations of ash deposition in the ocean,” Beinart said. “But there are many cases where scientists are looking at similar events in the fossil record and trying to piece together what happened.” The team’s observations offer a rare window into the process’s first stages.

Thousands to millions of years from now, perhaps scientists will study fossils of the creatures buried by the Hunga eruption.

Sink or swim?

Their original goal of studying the ecosystem largely dashed, the team quickly pivoted to investigate the eruption’s underwater aftermath. One of their more immediate findings counters long-standing ideas about how some creatures fare following similar events.

The fossil record suggests that crabs and other crustaceans are typically wiped out when their environment is suddenly inundated with ash. Scientists reason that the animals’ respiratory systems likely become clogged. However, Beinart and Arellano’s team noticed that crustaceans seemed to survive the Hunga eruption just fine and were scuttling across the ash that had entombed so many other animals. The team is still working out why crustaceans managed so well, contrary to expectations.

The team also collected more larvae of vent animals than expected. Arellano speculates that a new sampling system could have allowed them to gather more, or the event could have triggered the animals to spawn––something that’s known to occasionally happen following storms or other major disruptions.

“Or it could just be normal for this area,” Arellano said. “There haven’t been a lot of collections in this area before, so we don’t really have a baseline we can compare with.”

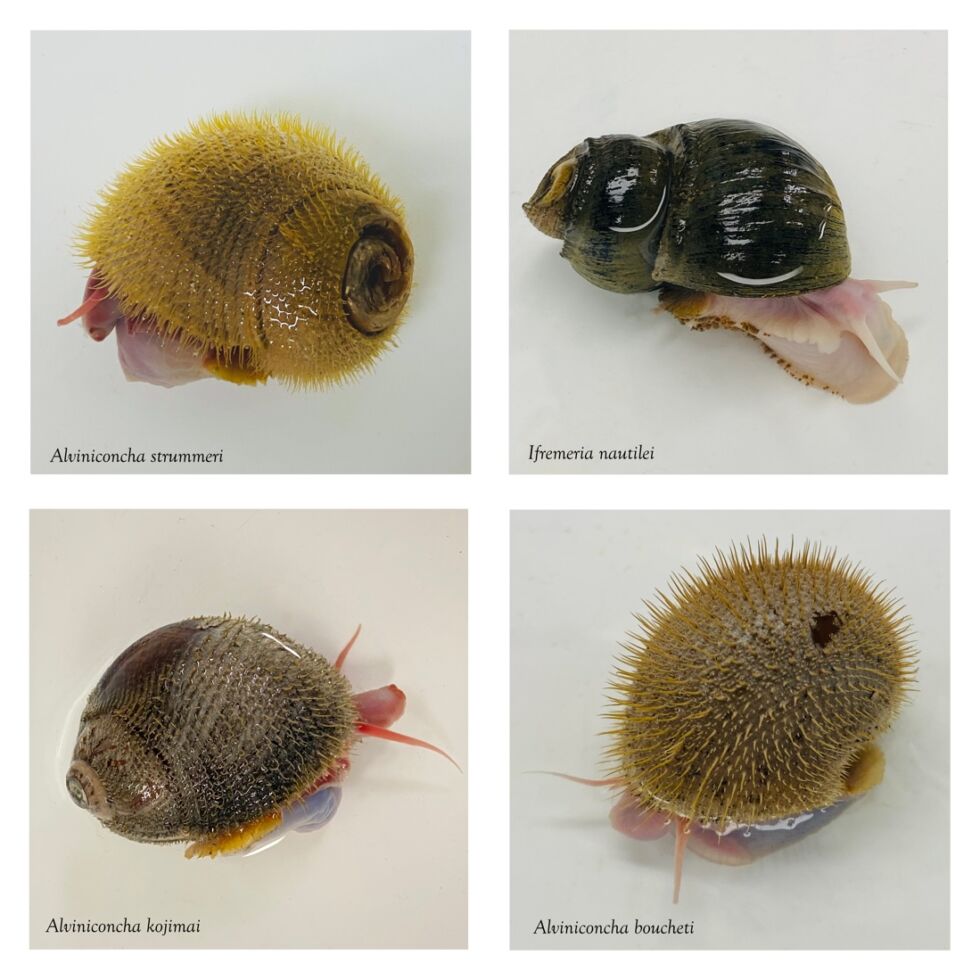

Dexter Davis (Western Washington University)

Among the samples the team collected, Arellano made the first documented observation of Alviniconcha snail larvae. Though these snails grow into animals that are dominant, foundational species at hydrothermal vents across the Western Pacific and Indian Oceans, no one had ever seen their larvae before. These creatures host chemosynthetic bacteria in their tissues that provide the bulk of their nutrition via chemicals in hydrothermal vent fluid.